are you listening? by Tillie Walden

are you listening? by tillie walden

[If you just want to read about the book, skip to paragraph five! Full of spoilers, if that is a thing you are concerned with.]

I started this post in Boston’s South Street Station, where I was waiting for my Greyhound bus back to Northampton. I had just finished Tillie Walden’s are you listening?, which I bought at the Newbury Comics in Harvard Square. I was there with my friend Amy Berkowitz, helping her do research for her novel, but I also had my own secondary project, which was to visit some of the sites that I remember from the summer my family spent in Boston.

I was five years old; my younger sister was around two, and my mom was pregnant with my youngest sister. My dad had gotten an NEH grant to do some sort of translation seminar at Harvard, and we all stayed in a little efficiency. We didn’t have all of our stuff, and we were just sleeping on air mattresses, but it was the happiest summer of my early childhood. During the day my mom, my sister, and I bopped around Boston. My sister loved all the old church spires—she called them fairy towers. I loved collecting the little folded T maps and subway art, like the bronzed gloves, delighted me. We made way for ducklings and visited the Children’s Museum, with the milk bottle ice cream stand out front and the Boston Tea Party Museum.

My mom kept a journal for me (probably still in a pile in my parents’ house). I couldn’t write that well yet, so I would dictate, and she would write. I couldn’t write that well, but I was learning how to read. There was a comic books store near where we were staying, and I would get old superhero comics (Green Lantern, Superman, the Flash) and I seem to remember my sister was partial to the bin of little rubber animals. The Michael Keaton Batman movie had just come out, and I remember the comic bookstore habitués arguing about it in thick Boston accents. And then the summer was over, and we went back to Texas, where we had lived before, and where I continued to live until my mid-twenties.

So, Amy and I go to the comic bookstore some 32 years later. She thinks it might make a good workplace for one of her characters and I think it might be the one from my youth. “Recommend me a graphic novel,” I ask them. “What do you like?” they asked. “Something queer and witchy,” I said. They steered me over to their queer section and I found Tillie Walden’s are you listening?. It’s more magical realism than witchy, but I’m not quibbling. Besides, when I flipped it open, I found out that Walden is from Austin, Texas, where I was born. And she went to the Center for Cartoon Studies, which I believe is where my cousin and his wife went to school. For those reasons alone, I had to buy it.

The book begins with somewhat fantastic map of Texas (the cities and towns are real, but not situated in their actual geographic locations). In the center of the map is an epigraph from Adrienne Rich’s poem “Itinerary,” “The guidebooks play deception; oceans are / A property of mind. All maps are fiction, / All travelers come to separate frontiers.” My complicated feelings about Rich notwithstanding (suffice to say, she was no great friend to trans women—Joy Ladin’s “Diving Into the Wreck: Trans and Anti-Trans Feminism” is a great piece that reckons with this), this quote is perfectly apt for are you listening?

are you listening? is a narrative in motion. It begins with Bea, an 18-year-old girl, who is running away from home. Bea gets picked up by Lou, a neighbor who knows her family because she has fixed their cars at her auto shop. Where are they both headed? Bea says McKinney, but that’s just where the pack of gum Lou bought her was made. It doesn’t take Lou long to figure out that Bea doesn’t have a destination besides away, or for Bea to understand that Lou has something pressing down on her chest, too.

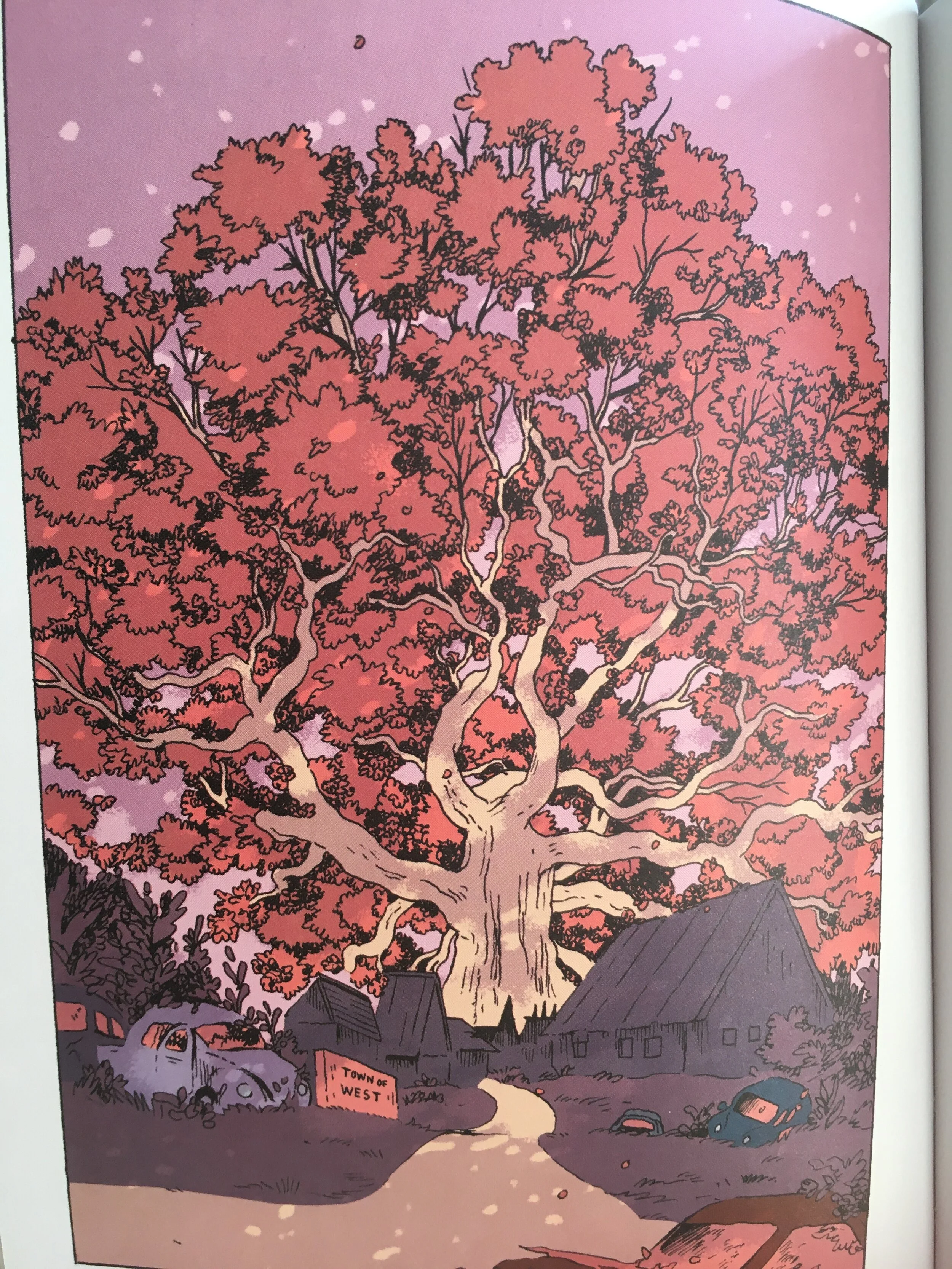

Lou’s ostensible destination is San Angelo, to visit her great aunt. She ends up invited Bea to make the trek with her. Along the way they pick up a white cat named Diamond, who gives an added purpose to their trip. Diamond has a collar and a tag with an address in a city neither of them have heard of before in a town called West, West Texas. Of course, if you’ve made the trek between Austin and Dallas, you have probably stopped at the West in Central Texas, to pick up kolaches and chleb at the Czech Stop, but West, West Texas turns out to be a more of an oneiric than a literal destination.

They both have their traumas, but what they do feels like the opposite of trauma bonding which, as I understand it, is too fast, and too predicated on a shared wound. Lou and Bea’s meeting is fast, but they are able to trust each other, make a healing space, and, in the end, to part ways as individuals. are you listening? speaks to how much people in transit can do for each other.

The transit feels like an important part. This is a road novel, and Texas is a place of long roads. In any narrative that goes from one region of Texas to another, there are going to be vast expanses of road and sky. Diamond’s person, when they finally find her, says this, “Well, West Texas is the perfect blend of giant and tiny. The land, the sky…it’s got its own mind, its own heart.”

When Lou teaches Bea how to drive, she is also showing her that autonomy and independence is within reach. I also think about what my main man Bachelard says about the house protecting the dreamer. For Bea and Lou, the car and the camper protects the dreamer. It’s where they sleep, piss each other off, come out to each other (a first for Bea!), where they make a provisional but safe home for each other and for Diamond.

And Diamond, like a cat in a Murakami novel (or, if you prefer, any cat), is very sensitive to energetic change. She ‘gets loose’ several times in the journey, but when she does she leads the travelers to a crevice underneath the roots of a tree, and to a warm mysterious indoor pool where Bea is finally able to share the details of her story with Lou.

The safe, womb-like environment of the car is assailed by the nefarious Department of Road Inquiry, who are after Diamond, for reasons that become clear later in the book. Finally, this environment cracks painfully open, but in such away that allows both Bea and Lou to re-emerge as individuals—but only after they return to their own roots, in the form of pivotal stories from their youth.

There’s a prominent tree theme in this book. Lou and Bea both have tree stories. For Lou it has something to do with being included—wanting to be up in the tree house where a girl (the first girl she liked?) was. For Bea, it’s about climbing to the top of the tree in her family’s yard (I’m thinking of the magnolia in front of my grandparents’ old house in San Antonio)—a gesture of independence—getting scared, falling, and not being caught by her father.

The funny thing about this tree leitmotif I guess you would call it is that it stretches between the book and my frame story about coming to read it! If you remember paragraph two, I mention the bronze gloves in the Porter Square T station delighting me as a five year-old. Well, turns out this is a piece called Glove Cycle, created by the artist Mags Harries the year I was born. According to Glove Cycle’s Wikipedia page:

Initially her concept revolved around bronze tree roots appearing to come through the walls and into the stations. This idea was turned down by the architects of Porter Station for bringing attention to the fact that the station is deep underground. Harries stated, "The whole philosophy of subway stations, it turns out, is to make them seem as un-underground as possible," something the tree roots idea would be the exact opposite of.

“Well, this has been great.” Lou gripes when they arrive at the address on Diamond’s collar, “We came all this way for a fucking TREE.” Harries arrived at her Glove Cycle after the Spring snow melt started to reveal lost gloves frozen beneath the snow. Arguably, the gloves in the T station are a kind of root down into the past—I know it was the gloves of passengers that emerged in the Spring thaw that inspired Harries, but I can also imagine them as the gloves of the workers who built the station. Either way, the gloves are spaces that were filled with clenched, held, gesturing hands—places of warmth and safety. Lou and Bea need to return to places of warmth and safety (or where warmth and safety should have been) in order to move forward on their own path.

What I am always longing and searching for are queer routes I can take back to my past in Texas. But journeys back into the past can be perilous, and books like this can function for readers the way that the car and the camper do for Lou and Bea. And now that I think about it, books like this one can function the way Diamond does, too: magicking new paths forward—of escape, when it’s necessary, and ultimately, hopefully, of possibility.