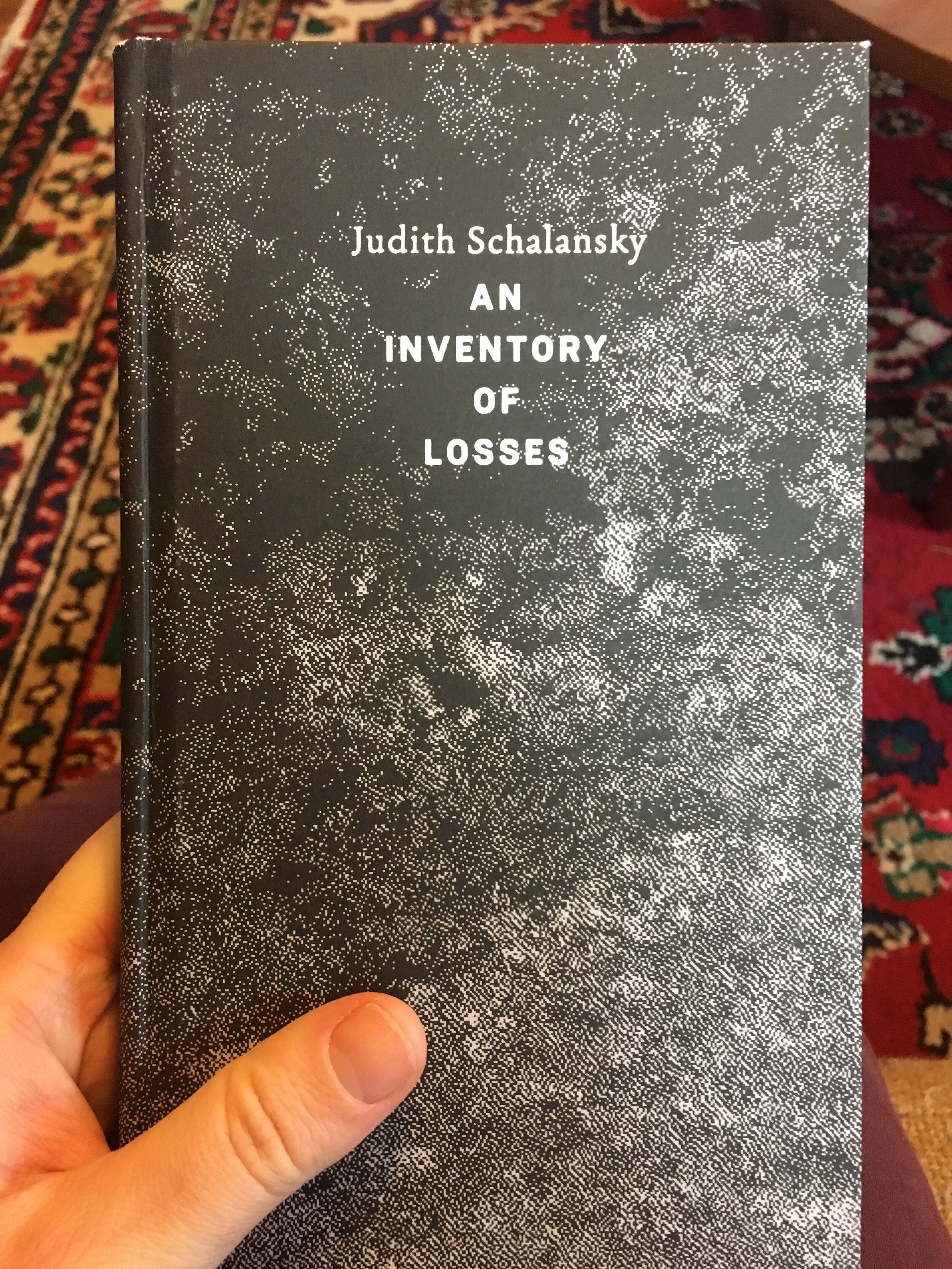

Judith Schalansky’s An Inventory of Losses, translated from the German by Jackie Smith (New Directions, 2020).

Judith Schalansky’s An Inventory of Losses, translated from the German by Jackie Smith (New Directions, 2020).

In December I drove to Cambridge, MA from my home in Northampton to pick up the library of my ancestors. This is a flowery way of saying a tank from the collection of genetic materials I stored before I started taking hormones, in case my partner and I wanted to try to have a child (something we are now actively trying to do). The past two times, the tank has arrived by courier, but for logistical reasons, this time I found myself doing the pickup. It was sweet actually, because I got to put a masked face on the person in the office who is assigned to my case (I get the feeling that she is really rooting for us).

I had to wait for them to prep the new tank, so I took the opportunity to pick up a delicious Italian sub which I ate in the car. I wanted to make an afternoon of it, so I dropped by one of my favorite Boston-area bookshops, Brookline Booksmith (this is not sponcon…just a bookstore I like). This is all I ask of a vacation really: to eat a delicious sandwich and to stick my head inside a bookstore! I didn’t want to spend too much time inside (it being a pandemic and all, if you are reading this in the future), so I made a beeline for the bottom floor, where I grabbed a copy of Cristina Rivera Garza’s El mal de la taiga, to attempt after I finish the Spanish translation of a YA novel I’m slowly making my way through, then stopped by the shop’s well-curated literature in translation section, where I grabbed An Inventory of Losses, motivated entirely by my trust in the booksellers’ curation and the book’s gorgeous design.

An Inventory of Losses is a well-proportioned clothbound book with a smooth matte paper that feels great in the hands. The cover is black but stippled with clouds of fine white dots. The title and authors name are silver. Each section of the book is preceded by a black page on which a picture corresponding to the section to follow has been faintly printed at the threshold of visibility—you can just sort of catch them if you hold the book at the correct angle (although a full “Index of Images and Sources,” and an “Index of Persons” are given at the end). Judith Schalansky is a book and typographic designer as well as an author so, although the bibliographic material doesn’t give any indication of the book designer, I suspect her of having at least had a hand in it!

The most reductive version of An Inventory of Losses’ premise is that it a literary cabinet of curiosities holding the absent-presences of a series of animals, structures, states of being, etc. Of her purpose, Schalansky writes:

This book, like all others, springs from the desire to have something survive, to bring the past into the present, to call to mind the forgotten, to give voice to the silenced, and to mourn the lost. Writing cannot bring anything back, but it can enable everything to be experienced. Hence this volume is as much about seeking as finding, as much about losing as gaining, and gives a sense that the difference between presence and absence is perhaps marginal, as long as there is memory.

Each of her entries encompasses both a thing and a place, e.g., Lesbos and The Love Songs of Sappho, as well as a temporality and a genre. That is, Schalansky moves between the English language (/marketing) distinction between fiction and non-fiction, into the realm of essay and story (travelogue, naturalist’s journal, etc.). This aspect of An Inventory of Losses—the movement through styles and genres—calls to mind books like Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler, although Schalansky focuses more on the archival and taxonomic modes. She treats the pleasures and problems of archiving in her preface, allowing that the world might be a giant archive of itself, and taking on the inherent paradox of any archive:

The organization of every archive may, like its prototype, the ark, be guided by the desire to preserve everything, but the undeniably tempting idea of transforming, say, a continent like the Antarctic or even the moon into a central, democratic museum of the Earth in which all cultural products are accorded equal status is just as totalitarian and doomed to failure as the re-creation of paradise, a tantalizing primal object of longing kept alive in the beliefs of all human cultures.

This allusion to the idea of the moon as a “central democratic museum of the Earth” is no tossed off fancy but a hint at the book’s final section, on the Lacus Luxuriae and Kinau’s Selenographs, which imagines just such a fantastic institution at length. The confusion between Gottfriend Adolf Kinau, “a priest and amateur astronomer from Suhl in Thuringia,” and “C.A. Kinau (?—1850). Botanist and selenographer,” who seems only to have existed in the 1938 Who’s Who in the Moon is noted the italicized prefatory remarks to this section.

This selenographic doppelgänger leads me, if obliquely, to the “unknown (or apocryphal)” “Chinese encyclopedia called the Heavenly Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge” which Borges cites in “John Wilkins’ Analytical Language” (translated by Eliot Weinberger and collected in Selected Nonfictions):

In its distant pages it is written that animals are divided into (a) those that belong to the emperor; (b) embalmed ones; (c) those that are trained; (d) suckling pigs; (e) mermaids; (f) fabulous ones; (g) stray dogs; (h) those that are included in this classification; (i) those that tremble as if they were mad; (j) innumberable ones; (k) those drawn with a very fine camel’s-hair brush; (l) etcetera; (m) those that have just broken the flower vase; (n) those that at a distance resemble flies.

The miscellanies of Borges and Alberto Manguel (in The Library at Night, for example) are present in Schalansky’s concerns and methods, as well as those of, say, Eliot Weinberger and Guy Davenport (and historically, John Wilkins, subject of the Borges piece quoted from above) , in that she shares their erudition plus a wide-ranging curiosity. Since I’m given to etymological thinking, I turn to the etymology of the word miscellany and am astonished to find that beneath Latin’s miscellanea as “a writing on miscellaneous subjects” (and so, basically, what it means today), there is an early meaning of “’meat hash, hodge-podge’ (food for gladiators).” This is astonishing because Schalansky’s chapter on the Caspian tiger is set in ancient Rome and imagines the passage of one of this species from the periphery to the center of imperial Rome, to the coliseum, where she is goaded to fight a lion in the coliseum.

In Schalansky’s care for the specificity of vocabularies within their contexts (literary analogue to archaeological remains), I am reminded of Predrag Matvejević’s Mediterranean: A Cultural Landscape (translated by Michael Henry Heim) and Robert MacFarlane’s Landmarks. Re: the latter of these two, take this paragraph from Schalansky’s section, “Greifswald Harbor:”

I follow the watercourse eastwards past tousled clumps of withered reeds. A Haflinger mare and her foal graze in a lush green paddock. Warblers babble from hedgerows newly in leaf behind drifts of gangling stinging nettles. From a farm building comes the whine of a chainsaw. Its rising and falling din accompanies me for a long while along the small dike streaked lavender gray with vernal grass, and mingles with the call of the cuckoo, clear as a bell, from the green-tinged white willows on the south bank. When I return its echo-like call, it hisses like a cat and flies from tree to tree in search of its rival. Above it, in the higher reaches, three gray herons drift solemnly, with angled, unmoving wings towards the bay. House martins zigzag busily back and forth over the rippled surface of the water, on which the occasional lily pad floats. Lupins hold their pale-blue flower spikes majestically aloft. Herbaceous speedwell with its little bluish-violet flowers and the tiny feathery shoots of yarrow appear dainty and fragile by contrast. Rotting amongst the fibrous broadleaf plantain is the scaly-blue gleaming rear end of a half-eaten perch, which must have been left behind by an osprey. Lanky bittercress dots the hay meadows birch white. Caramel-breasted whinchats flit, chirping, from stalk to stalk. From the quivering reeds comes the vehement call of the reed warbler, followed soon after by the melodious piping of the golden oriole from a nearby wood. (183-184)

I imagine Jackie Smith translating this section with the original text in one hand and a field guide to the plants and flowers of northeastern Germany in the other! (Not wanting to stop and look up every herbaceous speedwell and caramel-breasted whinchat that came along, I took it on faith while I was reading that these things exist and that Schalansky is not putting us on). Not only this, but Schalansky shares with MacFarlane and Rebecca Solnit that she is a rambler of the first order.

To be continued!

PS I’m a Bookshop affliliate on the off-chance that I can squeeze a sous or two from my reading and blogging, so that’s why I’m linking there, but obviously don’t forget the library!